Ask anyone in the spirits and wine industry, and you’ll hear that agave spirits—principally tequila—are selling like crazy and gradually taking over retail shelf space from other categories (sorry, brandy and rum). According to Statista, U.S. sales of tequila more than doubled over the past decade, rising from 12.3 million 9-liter cases in 2012 to almost 30 million in 2022. There’s more to agave spirits, however, than tequila. Based on industry stats and my informal observation of consumers shopping at Pinnacle Wine & Liquor, younger consumers especially are all about this thing called mezcal.

There’s only one problem: At tastings I pour, most consumers (especially of a “certain age”) have no idea what mezcal is. I’m here to help.

If you love tequila, peaty Scotch whisky, or gin you’ll probably love mezcal, too. Here’s what it is, a little about how to use it, and a bit about the difference between mezcal and tequila.

What’s the difference between mezcal and tequila?

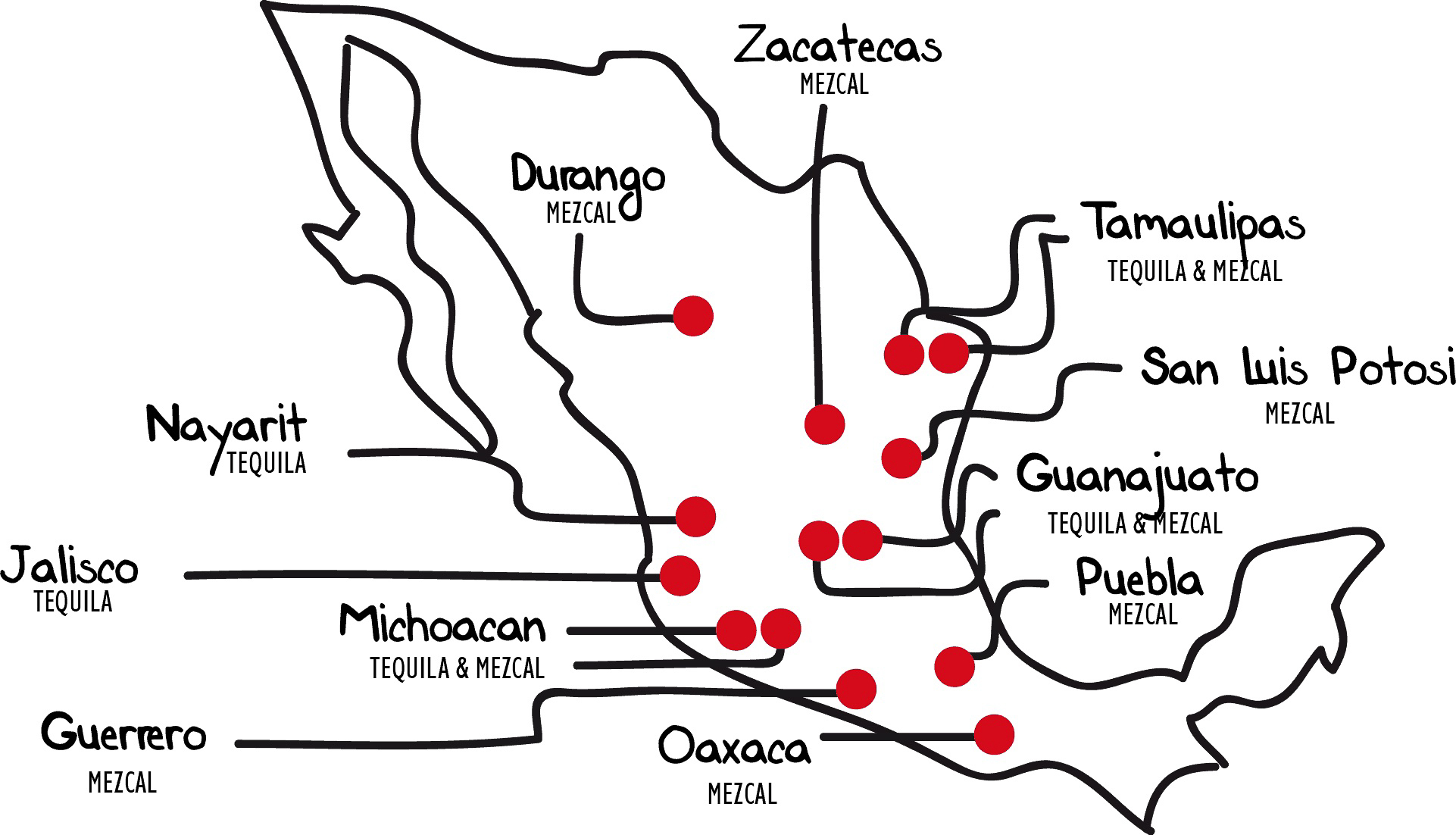

The best way to regard these two categories of agave spirit is that tequila is a very specific type of mezcal. The Mexican regulatory body Norma Obligataria Mexicana (NOM) dictates that tequila may only be made with “blue agave” (Agave tequiliana Weber), while mezcals may be produced from dozens of other specified agave species. Also, the legally defined production zones for tequila are significantly smaller than mezcal’s—portions of only five Mexican states—and the production zones overlap only very slightly. Most tequila is produced in the state of Jalisco (“ha-LEES-ko”), and most mezcal is produced in the state of Oaxaca (“wa-HAH-ka), although there are legal mezcal production zones in eight other states as well.

What is mezcal?

In the pre-history of spirits, “mezcal” was a generic term applied to any beverage fermented or distilled from any species of agave plant, of which there are more than 200 (although only 20-40 species are currently harvested for production of mezcal as we know it today). Agave, we should note, is a unique genus of succulent plants that are indigenous to what is now central and western Mexico but commonly found in the American Southwest, across Mexico, and further south in Central America.

For centuries, as far back as the Aztec and Mayan cultures, mezcals were considered ritual beverages and consumed primarily by spiritual leaders—possibly even used as an opiate to help humans being sacrificed relax and, um, appreciate the experience—or at least not mind it as much. Even today in Mexico, consumption of mezcal is largely reserved for major religious holidays such as Easter, Christmas, Day of the Dead, baptisms, weddings, funerals, or important family fiestas.

Here in the United States, we’re not even close to that reverent in our use of it.

Over the past 50 years, the NOM established definitions, production standards, and production zones for agave beverages including mezcal and tequila. The Mexican standards and definitions are recognized by the U.S. government and the European Union; a spirit may only be labeled mezcal (or tequila, for that matter) if it’s produced in Mexico in conformance with Mexican law.

All bottles labeled mezcal must be distilled from a fermented ‘mosto’ (“must,” or what American whiskey makers call “mash”) of 100 percent agave from an approved species (dozens are allowed) and produced within one of the zones defined by the NOM. No export of bulk mezcal is allowed; it’s all bottled within the mezcal production zone.

There are three categories of mezcal—and six classes. (Bear with me!)

Categories

- Mezcal: Produced with modern methods aimed at efficiency in production, such as large steel ovens or autoclaves, stainless steel fermentation tanks, cultured yeasts, diffusers, and all types of stills.

- Mezcal artesanal: Must be produced in pot stills, and diffusers are not allowed; traditional methods of roasting, shredding, and fermentation are allowed but not required.

- Mezcal ancestral: Must be made entirely by ancient traditional methods—agave piñas roasted underground and shredded by hand only; mosto fermented naturally (i.e., no commercial yeast inoculation) in wooden or clay vessels, or in animal hides; distilled in traditional clay pots or wood.

Classes

- Joven (“hō-ven”), or blanco: White, unaged (the most traditional, most common)

- Reposado: Aged at least two months but no more than a year in wood barrels

- Añejo: Aged at least one year in wooden casks

- Madurado en vidrio: Aged in glass

- Abocado con _____ : Flavored with _____, as in flavors added after distillation

- Destilado con ______: Distilled with _____, where additional ingredients (such as fruits, nuts, or meats) are distilled into the mezcal (Keep a Spanish-English dictionary up on your phone while browsing so you’ll know what it is!)

Again, most mezcal is produced in the state of Oaxaca, and almost 90 percent of the agave used in mezcal production is Agave espadin. However, many of the more than 20 mezcals we carry at Pinnacle Wine & Liquor are based on varieties other than Agave espadin. The tremendous variety of agave species and production methods employed for mezcal offers a wide diversity of flavor profiles to explore. (To learn more about mezcal and other agave spirits, here’s an excellent website.)

Why do mezcals have such a smoky flavor profile compared to tequila?

Most of a mezcal’s flavor derives from the species of agave employed, and some species intrinsically read a bit smoky in the nose and on the palate. Mezcals produced artisanally—i.e., with agave piñas baked in covered pits—so completely absorb smoke from the smoldering fire that smoky aromas and flavors survive the crushing, mashing, and distillation steps to inhabit the finished mezcal. Piñas of blue agave for tequila, on the other hand, are typically baked in above-ground steam ovens that are traditionally brick, although other materials are allowed—no smoke is involved in most cases.

Who would enjoy mezcal?

Anyone who already loves other strongly flavored spirits, such as gins or peaty Scotch whiskies, might find mezcal’s bold flavor profiles enjoyable as well. (That’s very much a two-way street; if you already love mezcal and haven’t tried flavorful gins or Scotches, give those a try!)

Do I really have to ‘eat the worm?’

No, and it’s hard to find agave spirits with worms in the bottle now anyway. But if you had to eat it, it wouldn’t kill you. Here’s a great article all about that worm thing.

How to use mezcal in your home bar:

Lots of mezcal fans enjoy sipping it neat or over a little ice with a twist of lime, but mezcal can also add layers of flavor to lots of cocktail recipes. Try my personal favorite Margarita recipe, a Pastry War Margarita (worth it for the history alone!), or go all in with an outright Mezcal Margarita. The Naked and Famous is a delicious and very popular marriage of mezcal, Aperol, Yellow Chartreuse, and lime. The 1910 cocktail teams mezcal with Cognac, maraschino, and a hearty Italian vermouth. With the holiday season approaching, consider a cocktail I call “Snowbound in Jalisco,” but which I could also have called “Snowbound in Oaxaca.” It has as much mezcal as tequila.

Martini lovers, try swapping your gin for mezcal. Start with equal portions of mezcal and blanc vermouth (I prefer blanc with full-flavored spirits like this, but use dry if you choose) and adjust to taste. Finish it with a dollop of bitters (lime, lemon, or orange), a garnish of lime or lemon zest, and serve it up or over ice. Or combine mezcal with tequila (my go-to for this is El Tesoro) in the excellent Mex Martini.

Pingback: Cooks’ World/Pinnacle Liquor Cocktail of the Week: Peat’s Dragon | The Libation Lounge