“Can you tell me if this is gluten-free?”

This question comes up regularly at spirits tastings and seminars I conduct and from customers at Pinnacle Wine & Liquor, where I work part-time. Usually it’s about a vodka or whiskey; interestingly, the question seldom arises about gin or other spirits, although it very well could, as lots of spirits incorporate alcohol fermented and distilled from the grains of concern to gluten-sensitive people.

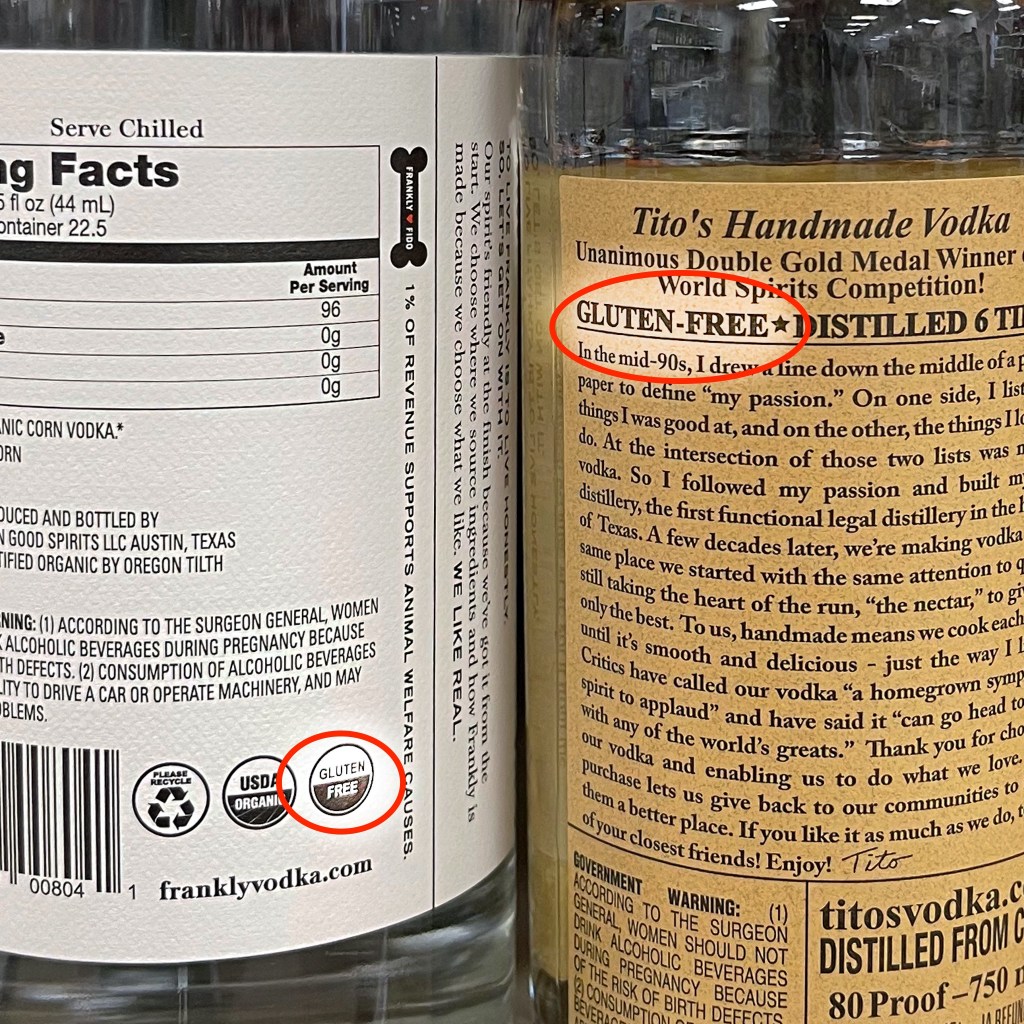

My perception is that the gluten question sometimes arises because some products, but not all, in certain categories include “gluten-free” on their label, leading gluten-averse consumers to wonder why that term doesn’t appear on others. Not everyone working in the spirits industry has a ready answer, and confronting the question can be an awkward moment. So here—at some length, apologies in advance—is my complete answer. It’s more than a typical customer is looking for, but I want to provide the full work-up for the truly curious and, especially, my friends in the industry.

SUMMARY

Gluten is a protein commonly found in the cereal grains often used to produce distilled spirits (e.g., wheat, barley, or rye). According to scientists, distillation removes all protein (including gluten) from a spirit if good manufacturing practices are followed. In fact, when gluten is heated, it long-chains (i.e., solidifies) the same way proteins in egg whites do when we cook them. That property is why gluten plays its structure-giving role in baked goods. In other words, the only way significant amounts of gluten can find its way into a distilled spirit is if it’s added for some reason after distillation, most typically through use of coloring or flavoring agents.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) regulate the labeling of foods as gluten-free, including alcohol beverages. Currently, if a food or beverage contains no more than 20 parts per million of gluten (i.e., 20 milligrams of gluten per kilogram), it may be labeled gluten-free. Spirits producers who wish to label their products gluten-free must be prepared to show they use good manufacturing practices, and the TTB may require a product to be assayed for gluten content using FDA-approved tests before approving gluten-free labeling.

If a spirit sold in the United States is labeled gluten-free, you can be confident that it meets FDA and TTB standards. Not all spirits producers pursue gluten-free labeling for their gluten-free products, but if any distilled spirit hasn’t been modified after distillation and aging in wood—other than dilution with pure water to achieve bottling strength—you should be confident that it is gluten-free.

DISCUSSION

The pre-science: What gluten is (not just what it does)

You probably already know that gluten is a substance commonly found in the cereal grains—e.g., wheat, barley, or rye, which are prominent in production of distilled spirits—and that it poses a debilitating health threat for the 1 percent of Americans with celiac disease (97 percent of whom are undiagnosed, according to Johns Hopkins Medicine). Another 5-6 percent of Americans may have non-celiac sensitivities to gluten, according to some experts.

But wait—that’s about what gluten does, not what gluten is. What gluten is, is important to this discussion:

- Gluten is the common name for two proteins (gliadin and glutenin—but relax, there won’t be a quiz) united with each other by hydrogen bonds. Proteins are extremely complex substances with substantial molecular weight, and protein plus protein equals bigger, heavier protein.

- When gluten is heated, it ‘hardens’ by forming longer-chain molecules—just like the proteins in an egg white harden when we cook it. That’s why gluten plays the binding role in baking that it does; it helps foods keep their shape.

All of which is to say that gluten consists of relatively heavy, non-volatile protein molecules. It doesn’t boil, especially not at the relatively low temperatures where water (212oF) or ethyl alcohol (173oF) boil. It hardens.

The science: How would gluten get into a distilled spirit?

It’s worth understanding the basics of how a spirit is made, and the key process in this discussion is distillation, which concentrates alcohol to create many of the adult beverages we love.

Before distillation, the alcohol is created by fermentation of raw source materials that are rich in either directly fermentable sugars (e.g., grapes) or starches that can be converted to fermentable sugars (e.g., potatoes, which don’t contain gluten, or cereal grains, which do).

Fermentation produces what’s variously called wine, distiller’s beer, or wash—a liquid or slurry with alcohol by volume less than 10 percent. The wash (we’ll go with that term) is then distilled as necessary to produce a distillate that’s anywhere from 25 to more than 95 percent alcohol by volume, depending on what kind of spirit is being made, what kind of still is being used, and how many times the spirit is distilled.

Within the still, alcohol and other volatile compounds boil out of the wash, rise through the neck of the still and then pass through coils where they’re cooled and condensed back into higher-alcohol liquid in another vessel.

Here’s the most important point: When sourced from cereal grains—again, typically wheat, rye, or barley—it is true that the wash going into a still contains gluten. But that’s where the gluten stays: in the still, not in the distillate. As noted above, gluten simply doesn’t boil and vaporize, so gluten never gets out of a still. Period, full stop.

While cereal grains are source materials for lots of distilled spirits, health authorities, regulators, and scientists all agree that distillation leaves gluten entirely behind. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the U.S. Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) both say it in as many words: “Distillation removes all protein (including gluten) if good manufacturing practices are followed.”

Therefore, there are two ways gluten may find its way into a bottle of vodka, whiskey, gin, or other spirit: 1) The producer fails to prevent cross-contamination of distillate with glutenous, undistilled materials, or 2) The producer purposely adds some other glutenous substance to the product after distillation is complete—a coloring, flavoring or blending agent, for example. In particular, caramel coloring is produced using barley malt or wheat and is permitted for use in many spirits, although the TTB requires disclosure on a spirit’s label if coloring materials are used. More on this just below.

When sourced from cereal grains—again, typically wheat, rye, or barley—it is true that the wash going into a still contains gluten. But that’s where the gluten stays: in the still, not in the distillate. As noted above, gluten simply doesn’t boil and vaporize, so gluten never gets out of a still. Period, full stop.

Does aging a spirit in wooden barrels add gluten?

Trees do not have gluten, so it isn’t possible for a spirit to acquire gluten from the wood itself during aging.

There is one caveat regarding barrels used for aging spirits (or wine), which is that traditional (i.e., archaic) coopering called for use of a wheat flour paste (sometimes called a glue, but it wasn’t) to temporarily seal the top and bottom heads of a barrel before filling it. It was temporary because the staves of a barrel, once filled with a wine or spirit, will swell and create a tighter seal than any craftsman could make even using a sealer. The pressure of expanding staves and barrel heads would, yes, ooze some of that wheat paste into a barrel’s contents.

Flour paste has given way in most cases to waxes or other non-wheat-based sealants, but even where flour pastes were used, the amounts and the degree of contact with barrel contents are considered minimal. I couldn’t find any articles or papers specifically regarding barrels used for aging spirits, but this article includes a statement from experts at Cornell University about the influence of wheat paste on glutens in wine, particularly comparing it with the impact of glutens in wine fining agents:

“The wheat paste provides only a temporary seal, and only a small portion of what is applied will still be in contact with the barrel contents… I would expect the amount of gluten on the inside of a 225 L barrel should be lower than that administered for red wine fining, both due to the small amount of exposed paste, and also because some of the paste would be lost prior to use. So, if there is any gluten, I predict it would be lower than results achieved with gluten fining trials.”

“And since gluten fining didn’t cause problems, it seems reasonable to expect that barrels with wheat flour paste wouldn’t either.”

As on other aspects of the gluten issue, this suggests that concerned individuals contact the customer service team at producers of a spirit of interest to ask for more detailed information on this particular matter.

The regulation: How can you be certain a spirit is gluten-free?

Who regulates and verifies claims regarding gluten content of a spirit?

The FDA sets the requirements and standards for labeling foods and beverages of all types as gluten-free, as well as the scientific testing methods for measuring gluten content.

The TTB is responsible for interpreting and applying those standards to all alcoholic beverages made or marketed in the United States. If you browse the TTB’s Ruling No. 2020-2 regarding gluten content statements, you’ll see that the two agencies work hand-in-glove to coordinate their regulations.

How accurate are the tests performed to detect gluten in a spirit?

Pretty darn accurate. The FDA standard (to which the TTB conforms) is that a food or beverage may be labeled gluten-free if the approved analytical tests find less than 20 parts per million (ppm) of gluten—i.e., 20 milligrams or less of gluten per kilogram of food. That standard is based on the FDA’s understanding of how much gluten triggers adverse health effects in celiac disease patients (granting that not all patients are entirely alike). But the point is also that the FDA-approved tests are sensitive to below the level of 20 ppm. Think of that measurement as trying to find 20 black marbles in a big box filled with a million otherwise white marbles. No, thank you; I’m busy.

How easy is it for a spirits producer to label a product as gluten-free?

The TTB must approve the complete label of any alcoholic beverage made or marketed in the United States, so producers submit their labels with an application and await approval any time they wish to make a change.

Here’s a portion of what TTB Ruling 2020-2 says about labeling products that meet the FDA definition of “gluten-free”, edited for brevity:

“ … because it is possible to verify the absence of protein or protein fragments (and thus gluten) in these products using scientifically valid analytical methods, TTB will permit “gluten-free” claims on distilled spirits products distilled from gluten-containing grains as long as good manufacturing practices are followed that prevent the introduction of any gluten-containing material into the final product.

“If a distilled spirits product is comprised of a distillate distilled from gluten-containing grains and of one or more protein-containing ingredients added after distillation, the finished product label may bear a “gluten-free” claim if the manufacturer is prepared to substantiate, upon request, the absence of protein in the distillate, the absence of gluten in the added ingredients, and the precautions taken to prevent cross-contact, including from storage materials that may contain gluten.”

Simply stated, a producer must apply for approval to use the gluten-free labeling and be prepared to prove compliance with current standards, and proving compliance comes with costs attached.

What common source materials for spirits are intrinsically gluten-free?

Examples of commonly used gluten-free source materials for distilled spirits are potatoes, grapes, sugar beets, corn (it’s a grain, but not a cereal grain—pay no attention to those Frosted Flakes in your cupboard), all forms of natural rice, and dairy products (yes, Virginia, there are milk-based vodkas).

Since it’s usually made from barley malt or wheat, what spirits typically include caramel coloring?

This is a hard question to answer very precisely, because while caramel coloring is permitted in many, many categories of spirits, producers don’t always use it, and in almost all cases where it’s permitted, the TTB requires disclosure of coloring material use on the product label. The simpler news is that use of coloring materials is expressly not permitted in certain categories including: Canadian whisky; Irish whisky; Scotch whisky; bourbon whiskey; any American-made whiskey identified as “straight” whiskey; unflavored gin; mezcal; tequila; and neutral spirits including unflavored vodka.

Further, if a producer chooses to add any coloring/flavoring/blending material, it may change the category of the spirit, and such use must be identified on the product label. For example, if a producer adds FD&C Yellow #5 dye to a straight bourbon, it’s no longer a straight bourbon; it’s a “specialty spirit” and would be labeled “Straight Bourbon Whiskey With FD&C Yellow #5 added.” (For more, see the TTB’s “Limited Ingredients” page and TTB’s Beverage Alcohol Manual Ch. 7)

The bottom line: Is “gluten-free” labeling hype or useful information?

It’s very useful information if you’re a gluten-sensitive person. If a spirits label says “gluten-free,” you can trust that it meets the established FDA and TTB standards.

However, some producers choose not to pursue gluten-free labeling for their gluten-free products, perhaps because it hasn’t occurred to them yet or because of the effort and cost to secure it. A spirits giant like Tito’s (only for example) can probably pay for testing and gluten-free labeling approval with loose change dug out of the CEO’s office sofa, but any unflavored, non-colored vodka is just as gluten free as Tito’s. Lots of perfectly fine small producers of spirits probably consider the cost of securing gluten-free labeling financially unjustified, even if foregoing it loses some sales.

So … even if a bottle of distilled spirit doesn’t say “gluten-free,” it may be anyway. First, look closely at labels for any disclosure of coloring, flavoring, or blending agents. When in doubt, you may want to contact a producer directly and ask if they add any gluten-containing substance to their product after distillation.

This is why people are suspicious of marketing hype about gluten, isn’t it?

Yes. A crass producer may consider gluten-free labeling just an attention-getting differentiator, and some certainly do; be skeptical of any producer that appears to make “gluten free” their entire pitch. But I’m disinclined to believe that many spirits producers are so cynical that they pursue it for competitive marketing purposes alone.

If you’re one of the 18-20 million Americans who have gluten sensitivity or believe they have, which is all that matters, gluten-free labeling is absolutely not marketing hype. When I’m pouring tastings or working at the store and the question comes up, I am not about to tell a customer they shouldn’t worry about it—especially not if they’ve reacted adversely to some specific product.

You gotta do you. But be you with good information. I hope this has helped.

References:

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Regulations:

Code of Federal Regulations: Title 21, Section 101.91, “Gluten-free Labeling of Food”

U.S. Department of Treasury, Alcohol Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) Regulations:

TTB Ruling 2020-2 (October 13, 2020): “Gluten Content Statements in the Labeling and Advertising of Wine, Distilled Spirits, and Malt Beverages”

TTB: Limited Ingredients, “Flavoring Substances and Adjuvants Subject to Limitation or Restriction”

TTB Beverage Alcohol Manual Ch. 7, Coloring/Flavoring/Blending Materials

TTB Beverage Alcohol Manual Ch. 4, Standards of Identity (U.S. legal definitions of the various distilled spirits)

Code of Federal Regulations: Title 27, Chapter I, Subchapter A, Part 5, “Labeling and Advertising of Distilled Spirits”

Other Related Articles:

Wine Enthusiast Magazine, “How Spirits Are Made” (Dec. 18, 2020)

Celiac Disease Foundation, “Gluten-free Foods” page

Beyond Celiac, “Is Liquor Gluten-free?”

Does Food Dye Have Gluten?; SFGate Healthy Eating Newsletter, Dec. 27, 2018

Additives That Have Gluten; SFGate Healthy Eating Newsletter

Wine, Lose or Draw; “No Gluten, No Problem” blog, Nov. 22, 2010